Spawning Process

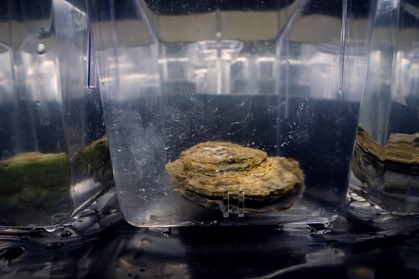

To begin the spawning process, mature adult male and female oysters, referred to as ‘broodstock’ are collected from Apalachicola Bay. These animals are cleaned thoroughly the day before the spawn to prevent the eggs and sperm from being contaminated by other organisms growing on the shells. On the morning of the spawn, each oyster is placed in its own tank and left to acclimate to the water temperature for 30 minutes. Once successfully acclimated, the oysters are stimulated to spawn through a process called thermal cycling, which alternates 30-minute cycles of cool and warm water to jumpstart the spawning process. Male oysters spawn by releasing a steady stream of sperm while female oysters puff out clouds of eggs. Once both the males and females released their respective gametes (reproductive cells), the hatchery team collects eggs from multiple females and adds sperm from multiple males to fertilize them. The fertilized eggs are then stocked into larval tanks.

To begin the spawning process, mature adult male and female oysters, referred to as ‘broodstock’ are collected from Apalachicola Bay. These animals are cleaned thoroughly the day before the spawn to prevent the eggs and sperm from being contaminated by other organisms growing on the shells. On the morning of the spawn, each oyster is placed in its own tank and left to acclimate to the water temperature for 30 minutes. Once successfully acclimated, the oysters are stimulated to spawn through a process called thermal cycling, which alternates 30-minute cycles of cool and warm water to jumpstart the spawning process. Male oysters spawn by releasing a steady stream of sperm while female oysters puff out clouds of eggs. Once both the males and females released their respective gametes (reproductive cells), the hatchery team collects eggs from multiple females and adds sperm from multiple males to fertilize them. The fertilized eggs are then stocked into larval tanks.

While in these tanks, the larvae are checked every day to make sure they are healthy and swimming. Their diet consists of a mix of concentrated microalgae once a day, and have a continuous feed throughout the night using a peristaltic pump. To promote a clean environment to grow in, the larval tank water is changed every two days. Hatchery technicians collect the larvae on sieves (fine mesh strainers) and separate the smaller larvae samples from the larger, faster growing larvae. Once separated, the larvae are restocked into clean water filtered to 1 micron (µm) to remove any outside sediments or organisms. About two weeks later, the larvae start to develop eye spots and a foot to find suitable substrate, which is also known as the pediveliger stage. During this phase, the team move the larvae to a setting tank filled with oyster shells. These tanks are then covered with a tarp to keep it dark and the larvae are left to set (to set means to settle on a hard substrate, such as oyster shell) for three days.

While in these tanks, the larvae are checked every day to make sure they are healthy and swimming. Their diet consists of a mix of concentrated microalgae once a day, and have a continuous feed throughout the night using a peristaltic pump. To promote a clean environment to grow in, the larval tank water is changed every two days. Hatchery technicians collect the larvae on sieves (fine mesh strainers) and separate the smaller larvae samples from the larger, faster growing larvae. Once separated, the larvae are restocked into clean water filtered to 1 micron (µm) to remove any outside sediments or organisms. About two weeks later, the larvae start to develop eye spots and a foot to find suitable substrate, which is also known as the pediveliger stage. During this phase, the team move the larvae to a setting tank filled with oyster shells. These tanks are then covered with a tarp to keep it dark and the larvae are left to set (to set means to settle on a hard substrate, such as oyster shell) for three days.

Larvae are photosensitive and tend to swim away from the light. By keeping the tanks dark, the oysters are able to set throughout the water column in the tank instead of simply settling at the bottom. To settle, the oyster will secrete glue from the foot to cement itself onto an oyster shell. The oyster will resorb it's vellum, the structure responsible for breathing, feeding, and swimming during its larval stage. It then starts to reorganize its body structure and form its gills through the process of metamorphosis. Within 24-48 hours, the once free-swimming oyster larvae is now cemented to its selected forever home, where it will remain for years. Once the larvae attach to oyster shells or other hard substrates, they become known as spat. The spat are then fed fresh algae from incoming seawater flowing through the tanks.

After another two weeks of spat growth, the hatchery technicians begin sorting the oyster shells full of newly settled spat. Less dense shells that hold 1-6 spat samples are sorted into aquaculture cages (150 spat per cage) for ABSI’s restoration experiments to assess their survival and growth. These had fairly low numbers of spat to avoid overcrowding as the oysters grow. The rest of the shells (with more than 6 spat) are then placed in biodegradable mesh bags (50 shells per bag) and placed on the substrate at the end of each experimental site. This less precise approach will be used to assess the value using bagged spat on shell as a restoration method.