Dr. Stan Kunigelis, director of the Math and Sciences Imaging Center at Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, TN, has been conducting research at the FSU Coastal & Marine Laboratory (FSUCML) since 1990. What began as the field component of marine biology courses for undergraduates, gifted and talented high school juniors and seniors, and an occasional special interest course, has now evolved into full-time graduate level research.

After pulling otter trawls for many years, Dr. Kunigelis began to ask about primary producers and primary consumers. He selected GPS defined sites between Lanark Shoal and Alligator Harbor to highlight habitat diversity within the estuary. And so began endless plankton tows!

Dr. Kunigelis and his team’s first step was to separate the planktonic world into zooplankton and others. They soon distinguished two co-dominant copepod genera, Acartiaand Labidocera. As director of the imaging center at Lincoln Memorial University, Dr. Kunigelis used the estuarine zooplankton in his electron microscopy courses to bring real world relevance into the classroom. Two things happened to take this study to the next level. First, curious students began to ask detailed questions about zooplankton feeding, reproduction, and life cycles. The second prompter was the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. All studies before 2010 spontaneously became pre-oil spill and everything afterwards, post oil spill. With 20 years of experience in the Apalachicola Estuary, the team’s new task was to compare 6 years of pre-oil spill plankton data to almost 5 years of post-oil spill information. This required them to first understand “normal” within population variation before looking for external causation.

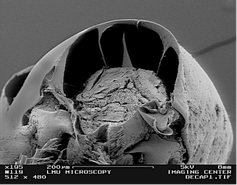

Jump forward to May 2015, and Dr. Kunigelis’ studies now focus on: 1) Comparative morphology of the mouthparts of Acartia, a suspension feeder, and Labidocera, an opportunistic raptorial feeder; 2) Identification of copepodid larval stages, with attention to morphological development between stages; 3) Cuticular lens comparative morphology of naupliar and transformed frontal eyes; 4) Cephalosome segmental anatomy of the proto-, deuto-, and tritocerebrum using freeze-cracking.

“With 20+ years of study at the FSUCML, I continue to use these facilities because of their convenience and ecological location,” explains Dr. Kunigelis. “Tremendous equipment and logistical upgrades under the Coleman administration are quickly bringing the marine lab into a leadership position.”