Groupers on the Edge

Life Cycles

Fishes in the Family Epinephelidae — known as Groupers — occur world-wide and are extremely important ecologically as well as economically wherever they occur. They include many of the top-level predators in warm-temperate & tropical ecosystems, associated with deep-water and shallow hardbottom reefs, following Pleistocene shorelines of the continental shelf and shelf edge.

Fishes in the Family Epinephelidae — known as Groupers — occur world-wide and are extremely important ecologically as well as economically wherever they occur. They include many of the top-level predators in warm-temperate & tropical ecosystems, associated with deep-water and shallow hardbottom reefs, following Pleistocene shorelines of the continental shelf and shelf edge.

Their relationships with the places they live are so striking in some cases that they appear to be acting as keystone species and ecosystem engineers — species which by their very presence or behaviors enhance the complexity of the habitat and thus the variety of the communities within which they live.

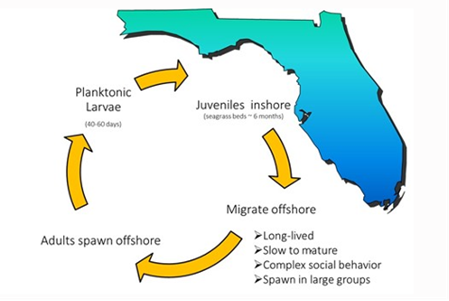

While each grouper species has a specific suite of traits — and individuals their own idiosyncrasies — there are a number of traits that they all share. Groupers, like many reef fish, spawn offshore on shelf and shelf-edge reefs. Their pelagic larvae remain in the open ocean for 40-60 days before reaching inshore nursery grounds. Once there, they transform into small juveniles, and remain in their nursery habitat for periods that vary from 5-6 months (Gag) to 5-6 years (Red Grouper & Goliath Grouper). They then move offshore to join adult populations. As they move from habitat to habitat, each life stage has very different requirements for being successful, occupying different niches relative to their size and their position in a food web, whether they eat plankton, bottom-dwelling crustaceans, or other fish.

As an overlay on this life cycle are life histories and behaviors that they also share. They are slow to mature and have complex social systems that provide cues for sex change. They also exhibit a high degree of site fidelity within their home ranges and to their spawning aggregation sites where they are easy to capture, particularly with the remarkable improvements in navigational gear that allows targeting very discrete locales.

Sex Change

Sex change in groupers is a one-way street, from female to male, and is initiated during spawning aggregations. For Gag (Mycteroperca microlepis) — one of the more important species fished in the eastern Gulf of Mexico — the period in which sex change is initiated is brief, occurring only during the late winter or early spring. At other times, males and females are separated, with males staying offshore on spawning sites while females move to shallower water. All of the reproduction in the population takes place in the brief time the sexes co-occur. So do all the cues for sex change. If there are too few males, then dominant females will change sex so that by the following spawning season, more males are available.

This combination of traits make them highly vulnerable to exploitation and habitat loss. There are currently no management plans in effect to adequately protect either their social structure or their nursery habitat. While marine reserves have proved an effective tool for protecting offshore spawning grounds, they have not been applied to nursery habitat which remains vulnerable to the effects of eutrophication, development, and industrial contamination.

Spawning Aggregations

For grouper, spawning aggregations vary in number, size, and location along a more or less continuous spectrum. Compare, for instance, Nassau grouper Epinephelus striatus, which has spectacularly large aggregations that occur at specific sites typically for just a few days around the full moons of December and January, with Gag Mycteroperca microlepis and Scamp Mycteroperca phenax, both of which form smaller aggregations over a broader area for about two or three months. Then there is Red Grouper Epinephelus morio, which does not appear to aggregate at all, and Goliath Grouper Epinephelus itajara, that aggregates in late summer and early fall (August - October) in aggregations of around 100 individuals.

For grouper, spawning aggregations vary in number, size, and location along a more or less continuous spectrum. Compare, for instance, Nassau grouper Epinephelus striatus, which has spectacularly large aggregations that occur at specific sites typically for just a few days around the full moons of December and January, with Gag Mycteroperca microlepis and Scamp Mycteroperca phenax, both of which form smaller aggregations over a broader area for about two or three months. Then there is Red Grouper Epinephelus morio, which does not appear to aggregate at all, and Goliath Grouper Epinephelus itajara, that aggregates in late summer and early fall (August - October) in aggregations of around 100 individuals.

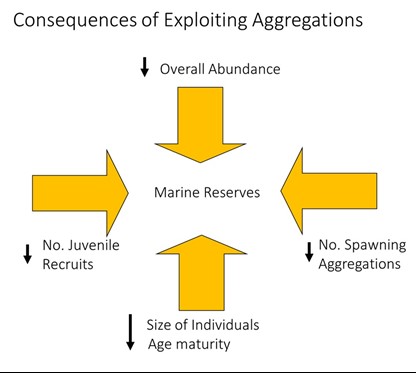

Fish that form spawning aggregations are susceptible to rapid overfishing when these aggregations are targeted for capture. The figure to the right depicts the consequences of this type of fishing. For Gag, the problem is compounded by the selective fishing of males because they remain on these sites year-round while females move on and off seasonally. The root cause of the decline in the number of males is the disruption of the social system of aggregations, since cues for sex change depend on social interactions.

It is during the immediate post-aggregation period that the percentage of transitionals (those fish in the process of changing from female to male) is highest.

The potential consequences of male loss are (1) reduced spawning opportunities for females; and (2) lowered fertilization through sperm limitation.