Normalized relations with Cuba could lead to clues to protecting our coral reefs. The reefs located in Cuban waters, especially a reef called the Gardens of the Queen (located 60 miles off the southern coast of Cuba), have remained in almost pristine condition for many years unlike most of the reefs in the Gulf of Mexico and other places around the United States. How have the reefs near Cuba managed to stay healthy ? And what can we do to help our own reefs? Through open collaboration with Cuban scientists and study of their healthy reefs, researchers could find answers to these questions and make strides in restoring marine habitats closer to home.

Here at the FSUCML, we have a scientist dedicated to protecting these beautiful and ecologically important habitats. Dr. Brooke is a member of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council coral working group, which was established by the Council to identify areas of deep coral habitat that should be designated as Habitat Areas of Particular Concern (HAPCs). Classifying an area as an HAPC acknowledges the ecological importance, vulnerability to degradation, or rarity of these communities. The coral working group identified ~50 priority areas throughout the Gulf of Mexico.

“These areas were divided into discrete zones (where abundant coral habitat is known to exist) and broad zones (where there is strong evidence for coral presence but that have not been surveyed). For the discrete zones, we also recommended that the Council implement regulations that restrict the use of bottom tending gear, which can damage fragile corals”, Dr. Brooke explains.

Regulating activities that damage the coral structure helps maintain the ecological function of the reefs, both in deep and shallow water.

“This is the beginning of a long process, during which stakeholders and the general public will provide their comments to the Council, who will ultimately decide which, if any, of the areas will be designated as HAPCs and whether the regulations on bottom gear will be implemented”.

This is an important first step for these coral communities because it will lead to further discussion about why we should care about these reefs and protect them.

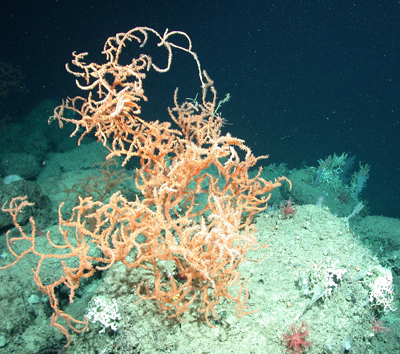

Shallow corals reefs help to absorb wave energy from storms, protecting shorelines from erosion and damage. They are biodiversity hot spots as well, creating complex three dimensional structures that serve as habitats to a diverse and abundant invertebrate and fish community, many of which are harvested for food. Deep corals provide similar services, but are less well-known than their shallow counterparts. Because life in the deep sea is colder, growth slows down and animals tend to live longer. Deep sea corals are the oldest animals on earth; some colonies of deep sea tree corals live for thousands of years and they serve as archives of past ocean conditions. Corals absorb seawater into their skeletons, so researchers are able to determine the chemical makeup of the seawater throughout a coral’s lifespan. These ancient animals can tell us what our oceans were like long before humans were keeping records, and may provide insight into how – or if - coral reefs will survive in the future.